Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

The 9/11 Memorial was dedicated on September 11, 2011 in a special ceremony for victims’ families. The Memorial opened to the public last September 12, 2011 with the reservation of a visitor pass.

Architect: MICHAEL ARAD, HANDEL ARCHITECTS

Landscape: PETER WALKER, PWP LANDSAPE ACHITECTURE

Location: Ground Zero, New York, United States

Opening: 12 Sep 2011

Oficial Site: 9/11 Memorial

From the architect:

“In the fall of 2003, “Reflecting Absence” was selected as one of the finalists in the World Trade Center Memorial design competition. I had created the design as a way of imagining a memorial that I myself might visit someday for mourning, commemoration, solace and hope.

Over the past eight years, all of us at Handel Architects, along with countless others in the design and construction industry, have worked hard to realize that vision and develop it to incorporate the aspirations and hopes of many more. It has been an incredible journey, simultaneously exhausting and inspiring, whose power we could not have imagined. The challenges of this project, so deeply emotional in nature, were the fuel that kept us going when we felt we could go no further. As the memorial opens to the public, and we step aside to allow the next chapter in the history of this site to unfold, we are proud of the work we have done, grateful for the opportunity to have made our contribution, and profoundly humbled by the responsibility that was entrusted to our hands. It has been an honor, a privilege, a duty, and, above all, a labor of love.”

MICHAEL ARAD, HANDEL ARCHITECTS

The design of the Memorial was selected through an international design competition that attracted over 5,200 entrants from 63 nations. Michael Arad won the competition in 2004, and joined Handel Architects as a partner shortly after, bringing the skills and talents of the office and its partners to assist him in developing the project.

The Memorial site offers a space for meditation and contemplation, centered around two reflecting pools that sit in the footprints of the original World Trade Center Towers. Lining the perimeter of each fountain is parapet of victims’ names, arranged and inscribed according to a system of “meaningful adjacencies.” The fountains rest within a new plaza that presents carefully chosen green space that acts as a sacred ground for those coming to honor the victims, while also integrating the Memorial into the surrounding city. The pools are clad in Jet Mist granite, and the names panels are made of bronze that has been treated with a ferric based patina. At night, the names are illuminated from within.

The project’s elegant simplicity conceals an incredible complexity of architectural design and engineering. The fourteen-acre WTC site will contain, in addition to the Memorial and the Museum, a Visitor Orientation Center, a new PATH train station, a Subway station, an underground retail concourse, an underground road network with security screening areas, five new office towers, and a Performing Arts Center. Most of these projects interlock physically and programmatically with the eight-acre Memorial site and have required close coordination between the various design teams.

DESIGN STATEMENT

The design of the Memorial emerged from my experiences here in New York, first as a witness to the events of that day in 2001 and then as a participant in the city’s compassionate and resolute response in the days, weeks and months that followed.

In late 2001 I began to sketch a pair of twin voids tearing open the surface of the Hudson River. As water rushed into these voids, they remained legible, clear and empty. This inexplicable, enigmatic image seemed to capture a sense of rupture, loss and persistent absence and stayed in my imagination. I found myself sketching and studying it and eventually constructed it in miniature scale as a small fountain/sculpture in 2002.

In 2003, when the competition for the design of the Memorial was announced, I revisited the idea of the twin voids, but sought a way to create a place of public assembly at the very site of the attacks where thousands had perished. I looked back to my own experiences as a New Yorker in the days that followed the attack, and the solace and connection I found in New York’s public and civic places such as Union Square and Washington Square. In particular I recalled a late night visit to Washington Square Park; I was unable to sleep, and as I walked about the eerily empty and quiet streets of lower Manhattan, I was drawn to the fountain at the center of this public space. There I found a few other people standing in silent contemplation. As I joined this circle– strangers both to me and to each other–I felt a sense of kinship and belonging; I was no longer confronting the horrors I had seen alone. I could not articulate it clearly at that moment, but I felt a bond form as I understood that I was a New Yorker now in a way I had never been before. Washington Square, as an open, public and civic place, brought me and others together in a remarkable way. It bound us together and united us in a wordless agreement. I had come alone to this square, but I was not alone there in the presence of others. Despair made way for hope, and fear made way for stoic compassion. These changes owed everything to the places that brought us together and made us stronger by virtue of uniting us – physically and emotionally.

The master plan that had been selected for the site and formed the basis for the competition guidelines had already articulated the importance of reintegrating the site into the fabric of the city, and suggested partially restoring the street grid through the reintroduction of Greenwich and Fulton streets, subdividing the sixteen acre site into four unequal quadrants. The largest of these, measuring eight acres, formed the site for the future Memorial. I wanted to amplify this move and create a public, civic plaza that drew on my own experiences here in the city. To that end I suggested that the site should be thought of primarily as an open plaza–a vast flat plain, punctuated by two large voids, deeply recessed reflecting pools ringed by waterfalls. I sought to bring together that image of the voids in the Hudson River and the experiences I had in Washington Square.

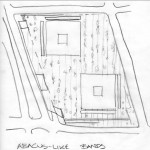

The jury for the Memorial competition saw the first iterations of this plaza as stark and austere. They challenged me to bring more vegetation and life to the site without losing the clarity of that first primary design gesture of the flat plain punctured by twin voids. I suggested adding bands of paving of irregular widths, which would unify the plaza and form an armature for placing trees along their length, in a manner analogous to the way beads can be placed at irregular intervals along the wires of an abacus.

This new element created a soft order, one that was not in conflict with the primary design gesture. At times, as one looks to the east or west, the trees will be clearly legible as long allées that snap into order; yet because of the irregular placement along the bands, as one looks north or south, the trees will become a diffuse and almost naturalistic random array. Just as important, the landscape adds new meaning to the design. Each of the voids is surrounded by a 10-foot-wide walkway, the outer edge of which is marked by a ring of trees. These trees coincide exactly with the location and dimensions of the former footprints of the Towers, measuring 212 by 212 feet. Columns of living trees will now stand where the steel support columns of the Towers once stood, and people approaching the voids of the Memorial will walk within the footprints of the Towers. I reached out to Peter Walker, whose work I admire, and asked him to help me implement this vision, and his expertise has helped realize these ideas.

Along the way we have had to solve many challenges. One of these was to ensure sustainability, an ethic that is deeply important to the Memorial, and that is mandated by the guidelines for the project. As realized, the Memorial plaza is now one of the most sustainable green spaces ever constructed. For this urban forest, flourishing near other green spaces that include the churchyards at Liberty Church and St. Paul’s Chapel and the planned Liberty Park just south of the Memorial, the majority of irrigation requirements will be met by harvesting rainwater collected in storage tanks below the plaza surface. This and similar energy-conserving aspects of the design are allowing the project to pursue Gold certification in the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED for New Construction program.

But of all the challenges we faced, none was more complex than the arrangement of the victims’ names around the reflecting pools. The encounter between visitors to the Memorial and the names of the victims was understood as a difficult and emotionally charged moment: an approach to the threshold that separates the living from the dead. I envisioned a profound moment of tragic comprehension as the scale of the voids – echoing the Towers’ dimensions – and the multitude of names surrounding each pool would together contribute to the creation of a moment of sad understanding. How could we arrange the names of the victims to reflect this terrible and enormous toll, while still honoring the individual and unique aspects of each and every loss? I wanted the arrangement of names to both reflect upon the victims’ lives while also marking their deaths. I decided that we should reach out to family members of the deceased and ask if they wanted the names of their loved ones to be arranged adjacent to other victims that they had known during their lives. This arrangement would imbue the piece with added meaning and complexity, reflecting on bonds of family, friendship, and workplace camaraderie.

This idea was met with apprehension at first, and concern over the complexity of its implementation delayed its acceptance until Mayor Michael Bloomberg became Chairman of the Memorial foundation in 2006. With his support and guidance we grouped the names of the victims into nine broad categories that reflect where people came from or where they were that day. This allowed us to place many of the victims’ names within the footprint of the Tower in which they perished. From there, we arranged the names in a careful order that reflected the wishes of the next of kin, but had the appearance of a random array of names. The strength of the arrangement is further enforced by the open space included around each name, providing each one with a space that is unique and individual while at the same time placing each name within the broader constellation of names. Each name is an island; together, they are an archipelago that rings the voids, emphasizing the individual and collective losses suffered that day.

MEANINGFUL ADJACENCIES

The question of how to arrange the victims’ names on the National September 11 Memorial was one of the most challenging of the design process. From early on, Michael Arad felt that neither an alphabetical list nor a random arrangement would be appropriate. He believed the way the names were displayed on the Memorial should convey a sense of the terrible, enormous toll of the attacks, but at the same time should honor the unique aspects of each of the 2,983 individuals who lost their lives.

His solution, which was ultimately adopted, is a system of “meaningful adjacencies,” which add meaning and complexity to the Memorial by reflecting the bonds of family, friendship and workplace among those who died.

The names are grouped in nine categories, which reflect the locations and circumstances in which victims found themselves during the attacks. Around the north pool are the names of those working in or visiting the north tower; those aboard Flight 11, which crashed into that tower; and the victims of the 1993 bombing of the north tower. Around the south pool are the names of those working in or visiting the south tower; those aboard Flight 175, which crashed into that tower; the victims at the Pentagon; Flight 77 victims; Flight 93 victims; and first responders.

But this was only the beginning. The victims’ next-of-kin were then offered the opportunity to ask that specific names be placed in close proximity to others. As a result, names of colleagues, friends and family are placed alongside each other within each of the nine larger groups, honoring more than 1,200 requests that were received.

Assembling the requests for meaningful adjacencies was painstaking, and the process of designing the arrangement was complex. But the result is a Memorial that speaks not only of the victims’ deaths but also of their lives.

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Construction 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Construction 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Construction 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Construction 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

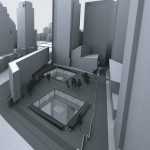

- Initial project 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Initial project 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Initial project 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Initial project 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Initial project 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Opening 9/11 Memorial – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

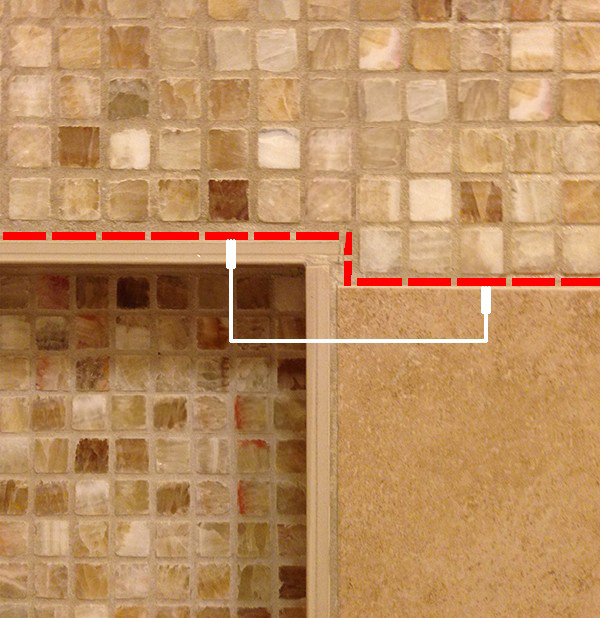

- Names Arrangement – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Names Arrangement – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Names Arrangement – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

- Names Arrangement – Michael Arad + Peter Walker & Partners – US

No Comments