Zaha Hadid passed away unexpectedly, suffering a heart attack in a Miami hospital where she was being treated for bronchitis. She was 65.

It would be disingenuous for me to claim I was an admirer of Hadid’s oeuvre. Doubtless she was an important figure within contemporary architecture, and in many ways a pioneer. As an Iraqi-born woman working in a field dominated by white men, Hadid overcame numerous obstacles to achieve rare prominence among her peers. Other women had enjoyed moderate success as builders, like the urban planner Catherine Bauer and the architect Eileen Gray, but never won the accolades Hadid did in her lifetime. Non-Western architects have likewise made only modest headway in the modern period. Gabriel Guévrékian, of Persian-Armenian origin, was one of the founders of CIAM in 1928, while the Chinese-born architect I.M. Pei perhaps alone can claim to rival Hadid’s accomplishments.

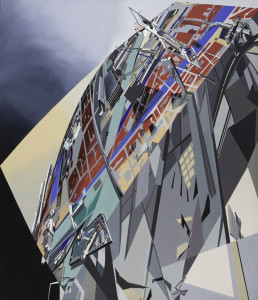

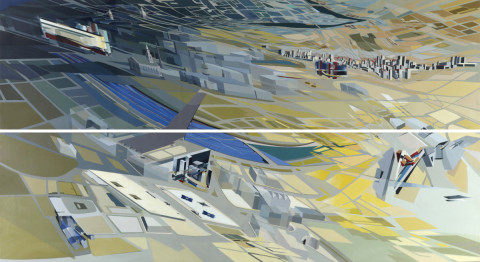

To be perfectly honest, I was much more torn up about the 2012 death of Lebbeus Woods. But he’d been sick for a long time. Woods was something of a mentor to Hadid when she was first starting out in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Her early architectural delineations — or “paintings,” as she called them — were often quite impressive on a formal level. She worked in much the same speculative vein as Woods or Daniel Libeskind. Incidentally, before he died, Woods devoted a short essay split up into three posts on his blog, all of which analyzed Hadid’s drawings:

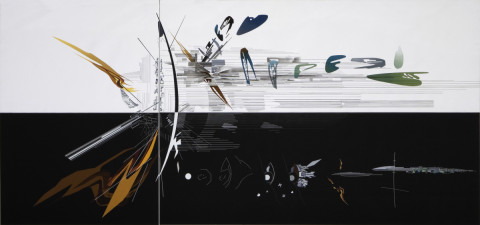

Hadid’s work of the eighties was paradoxical. From one perspective, it seemed to be a postmodern effort to strike out in a new direction by appropriating the tectonic languages of an earlier epoch — notably Russian avant-garde at the time of the Revolution — but in a purely visual, imagistic way: the political and social baggage had been discarded. This gave her work an uncanny effect. The drawings and architecture they depicted were powerfully asserting something, but just what the something was, in traditional terms, was unclear. However, from another perspective this work seemed strongly rooted in modernist ideals: its obvious mission was to reform the world through architecture. Such an all-encompassing vision had not been seen since the 1920s. Zaha alluded to this when she spoke about “the unfinished project” of modernism that she clearly saw her work carrying forward. With this attitude she fell into the anti-postmodern (hardly popular) camp championed by Jürgen Habermas. Understandably, people were confused about what to think, but one thing was certain: what they saw looked amazing, fresh and original, and was an instant sensation.

Studying the drawings from this period, we find that fragmentation is the key. Animated bits and pieces of buildings and landscapes fly through the air. The world is changing. It breaks up, scatters, and reassembles in unexpectedly new, yet uncannily familiar forms. These are the forms of buildings, of cities, places we are meant to inhabit, clearly in some new ways, though we are never told how. We must be clever enough, or inventive enough, to figure it out for ourselves — the architect gives no explicit instructions, except in the drawings. Maybe we, too, must psychically fragment, scatter, and reassemble in unexpected new configurations of thinking and living. Or, maybe the world, in its turbulence and unpredictability, has already pushed us in this direction.

Like Libeskind, but unlike Woods, Hadid eventually transitioned from paper architecture to the realm of built objects. Receiving major commissions around the world, she began to cultivate a complex, curvilinear, and organic style. Patrik Schumacher, her theoretical spokesperson, called it “parametricism.” Aided by new digital programs, which could calculate the area of contoured surfaces, Hadid developed a biomorphic expressionism that became her trademark. My opinion of these later structures is considerably lower than it is of her earlier, more suprematist-inflected buildings. I quite like the Vitra Fire Station in Weil am Rhein, as well as the Rosenthal Center in Cincinnati. Essentially I agree with Woods here: “In one sense, [computer-aided design] liberated Zaha, enabling her to create the unprecedented forms that have, by the present day, become her signature. In another, it brought an end to a certain intimacy and feel of tentative, almost hesitant expectancy, in her drawings and designs, that was part of the intense excitement they generated.”

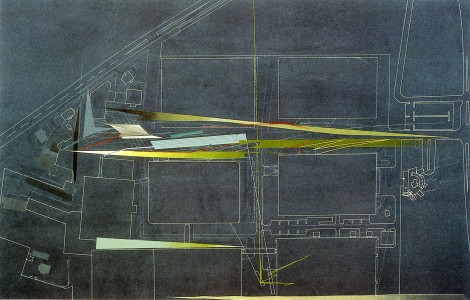

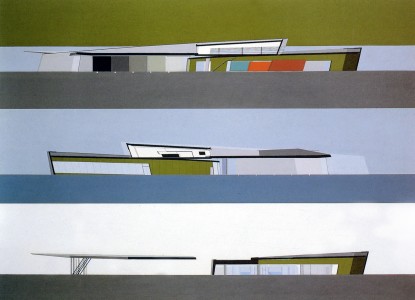

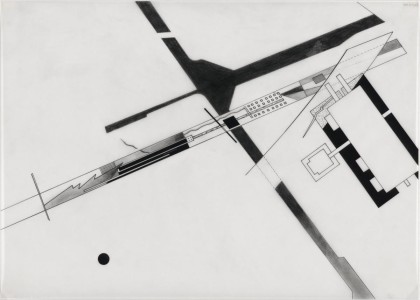

Below I am appending some extremely hi-res images of Zaha’s drawings. Longish essays by Hal Foster and Gevork Hartoonian, both insightful and making similar points about the prioritization of image and spectacle over building and tectonics, also follow.

In the last decade, Zaha Hadid has advanced from a vanguard figure in architecture schools to a celebrity architect with credibility enough in boardrooms to have several big buildings completed and several other projects launched. This upswing began in 2003 when her Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, her first structure in the United States, opened to wide acclaim, and it was confirmed in 2005 when her BMW plant center in Leipzig, which proved her ability to design for industry, was completed. In 2004 Hadid won the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize — the first woman to be so honored — and in 2006 she received a retrospective of thirty years of her work (paintings as well as designs) at the Guggenheim Museum. More recently, her Museum of XXI Arts (MAXXI) in Rome appeared to warm reviews in 2009, and there are other large commissions in the works, including office buildings and cultural complexes in the Middle East, an opera house in Guangzhou, and an aquatic center for the 2012 Olympics in London. Hadid can no longer be dismissed, as her critics were once wont to do, as a woman who stood out in a male profession on account of her brassy personality and exotic background (she was born in Baghdad in 1950). Indeed, for her proponents Hadid has done more than any of her peers to rethink old representational modes of architecture and to exploit its new digital technologies. It is this view I consider here, with special attention to her recourse to select moments in modernist art and architecture.

For several years after her 1977 graduation from the Architectural Association (AA) in London, Hadid had little work of her own. In this lull she turned to modernist painting, in particular the Suprematist abstraction of Kasimir Malevich. Hadid explored this work in painting of her own, which she regarded primarily as a way not only to develop an abstract language for her architectural practice, but also to render the standard conventions of architectural imaging (plan, elevation, perspective, and axonometric projection) more dynamic than they usually appear. Already in her AA thesis, an unlikely scheme for a hotel complex on a hypothetical Thames bridge, Hadid adapted the idiom of the Malevich “Arkhitektons,” plaster models, built up in geometric blocks, that he proposed in the middle 1920s for a monumental architecture in the young Soviet Union. This was only an initial gesture, but it was not an auspicious one, for, however enlivened with Suprematist red and black, the Arkhitekton blocks remain static in her adaptation. Nevertheless, her project was shaped: “I felt we must reinvestigate the aborted and untested experiments of modernism,” Hadid wrote in retrospect, “not to resurrect them but to unveil new fields of building.”

To recover the suspended experiments of the historical avant-garde was a principal strategy of neo-avant-garde art after World War II (think of the multiple remotivations of Dada alone). Of course, modernist art suffered a traumatic suppression under the regimes of Hitler, Stalin, and (to a lesser extent) Mussolini; as a result, such movements as Expressionism, Constructivism, and (again, to a lesser extent) Futurism became somewhat occluded, and a return to them could have the force of rediscovery and revaluation. The case of modern architecture is different: its suppression was not as severe, and, as key figures like Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, and Mies van der Rohe not only persisted but prospered in the postwar period, there was not distance enough to make them appear strange or new. Thus, for example, when young architects like Peter Eisenman and Richard Meier revisited Le Corbusier in the 1960s, it had little of the repercussive effect of a neo-avant-garde return; it did not reset the terms of discourse radically. Of course, there are partial exceptions to this general rule. Reyner Banham had urged designers of his generation to reconsider Futurist and Expressionist architecture, long sidelined by the functionalist and rationalist preoccupations of the International Style, and later in the 1960s another generation of designers began to explore the largely lost precedent of Russian Constructivist architecture. Hadid also probed this precedent at the AA with her teachers Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis, yet it was unusual for an architect to look to a painter like the Suprematist Malevich — and it was untimely, too, for by the middle 1970s advocates of a return to representation in postmodern architecture had begun to dismiss modernist abstraction in toto — and what more absolute apostle of modernist abstraction could one evoke than Malevich? At least in this respect, Hadid might be aligned with the different enterprise of postmodernist art, which sought to subject representation to critique rather than to restore it.

“I have ripped through the blue lampshade of the constraints of color, “ Malevich wrote in 1919. “I have come out into the white. Follow me, comrade aviators. Swim into the abyss.” This is a radical claim to non-objectivity, one that aims to negate not only all representation but any worldly association of color, not to mention the earthbound orientation of the traditional picture (with a vertical position that mirrors our own upright posture). Yet not all Suprematist paintings plunge so fully into the abyss: sometimes a residue of a referent remains in Malevich, and often his geometries still read as colored figures against white grounds, even when these grounds might also suggest a space beyond “the blue lampshade” of the sky. In her paintings Hadid exploits some of these ambiguities, such as how Suprematist forms can appear as horizontal or vertical and Suprematist spaces as recessive or shallow. At the same time she complicates these uncertainties, for often in her paintings perspective is not banished so much as multiplied, with the effect that different views exist within single images, and spatial axes are not only rotated but also warped, with the result that her planes run in various directions at once — from us, toward us, and at many angles and curves in between. Suprematist painting was once seen as a radical flattening of the picture plane; Hadid motivates it instead as a dramatic break into an indefinite space-time, in an attempt to “crack open” her objects, to “compress and expand” her spaces, to intensify and liberate her structures, all at once.

An early statement of these goals is her 1983 painting The World (89 Degrees), where, hubristically enough, Hadid transforms a section of the globe into a survey of her own projects to date, with the earth turned on its ear, minus — in a pointed deviation from rectilinear regularity — one degree. “The real world becomes Hadidland,” Aaron Betsky enthuses about this manifesto-painting, “where gravity disappears, perspective warps, lines converge, and there is no definition of scale or activity. This is not a specific scene of functions and forms, but a constellation of possible compositions.” Here, her longtime collaborator Patrik Schumacher also enthuses, Hadid announced a “new paradigm” of “complex curvilinearity.” However, if this is a new paradigm, it has its problems. To be sure, the turn to abstract painting was a striking move, but it rendered her designs pictorial, even weightless. Hadid points to this tendency in her own account of her early projects, where she writes of “floating pieces” of architecture “suspended like planets.” Once released, how are these structures to be regrounded? Malevich forged his abstraction not only by suppressing the referent but also by unmooring the viewer, in part through an extrapolation of aerial views that makes any subject-position difficult to imagine. This was a radical gesture in painting, but is it a valid one in architecture? Where is the subject, let alone the object, in this floating? At this early stage, however, such concerns did not count for much, and her provocation that representation was as important as construction advanced Hadid in architectural circles.

Hadid did deploy, as a materialist counterweight to the airborne idealism of Malevich, the Constructivism of Vladimir Tatlin. Already in the late 1970s this “opposition between Malevich’s Red Square and Tatlin’s Corner Relief” governed her designs for Koolhaas and Zenghelis (in their fledgling Office for Metropolitan Architecture), designs that strive to hybridize the different languages of Suprematism and Constructivism (the former concerned with the transcendental, the latter with the tectonic). Hadid pursued this unlikely synthesis in her own practice after 1979, too, especially in The Peak (1982-1983), her winning entry in a Hong Kong competition. She describes this unbuilt scheme, in which a resort complex is fractured into a cliff site, as “a Suprematist geology,” a paradoxical phrase that points to the tension between the principles represented by Malevich and Tatlin. Yet it was this very tension that positioned Hadid first to be included in the landmark “Deconstructivist Architecture” show curated by Mark Wigley and Philip Johnson at the Museum of Modern Art in 1988, and then to be tapped as the designer of the “Great Utopia” exhibition at the Guggenheim in 1992-1993 (where the old rivalry between Malevich and Tatlin was restaged).

For Hadid the next move was to demonstrate that her dynamic representations could be translated into actual buildings, and here again the proposals of Constructivism suggested a way to stitch together her complex geometries. It is also true that, as work began to trickle into her office by the middle 1980s, Hadid simplified her forms. Prow shapes were prominent in the designs of the late 1980s; they govern her first major buildings, a Berlin housing complex (1986-1993) and the Vitra Fire Station near Basel (1990-1994). In the early 1990s these shapes were joined by wedges and spirals, as in her Spiral House project (1991), and then in the middle 1990s by folds and ramps, as in her Blueprint Pavilion (1995) and her plan for a Prado Museum extension (1996). As with other architects in this new period of computer-aided design, her formal ambitions expanded with her technical capacities, and this conjunction soon allowed Hadid to imagine walls that emerge “in all directions,” as in her Wish Machine pavilion of 1996, and to propose skins that “weave and sometimes merge with each other to form floors, walls, and windows,” as in her project for the Victoria and Albert Museum extension in the same year. These devices can be dismissed as extravagant gestures, but they are not entirely arbitrary; in contrast to other architects given to idiosyncratic forms, Hadid worked to make her shapes appear as motivated generators of her structures and spaces.

In the beginning Koolhaas was a guiding star for Hadid: her decision to look back to neglected precedents in modernism was supported by his example, as was her tendency to develop one element in a program or a site as the key to an entire scheme; his attention to the metropolis at large also influenced her. Yet, in the matter of representations elaborated into buildings, Hadid revealed another affiliation, here to Eisenman. In the annals of architecture the elaboration of a representation into an object is hardly a novel operation: the application of single-point perspective was foundational to Renaissance architecture, for example, just as its complication was important to Baroque architecture (think of Brunelleschi and Borromini, respectively). Understood broadly (from El Lissitzky to Theo van Doesburg, say), Constructivism also exploited perspectives and projections as generators of design. Yet Eisenman went further in this direction; sometimes in his early houses his projections seem to determine his buildings. Hadid went further still, as she pushed familiar modes of architectural representation — not only isometric and axonometric projections but also single-point and fish-eye perspectives — into strange explosions of structure and “literal distortions of space.” At this time, too, architects like Frank Gehry had developed the form-making of avant-garde design to such a point that it had to confront (once again) its own modernist dilemma: how, given this apparent freedom, to motivate architectural decisions? It was largely an engagement with modes of representation that saved Eisenman and Hadid from the willful shape-changing of Gehry and his followers.

In the midst of her “literal distortions of space,” Hadid revealed a drive to challenge the assumed verticality of architecture, to open up building on its horizontal axis (already in 1996 she imagined a bridge for London as “a horizontal skyscraper”). In principle this lateral opening can render architecture less monumental and more dynamic; it can also pull the building across its setting in a way that complicates both the relation to its ground and the threshold between its interior and its exterior. It is primarily in this manner that Hadid expanded her practice from discrete structures to “new fields of building,” in which her schemes seem to emerge out of tensions immanent in the sites. Sometimes, too, she ran this transposition of axes the other way around: Hadid “flipped up” the ground “to become a vertical plane” as early as a 1990 project for an Abu Dhabi hotel, and she did much the same thing in her 2005 proposal for a Louvre extension for Islamic art. This vertical-horizontal play became central to her architecture, and it made her folds, ramps, and spirals appear as structural elements as well as stylistic flourishes — elements that mediate not only between the levels of a given building but also (again) between interiors and exteriors and among structure, site, and city. This kind of axial transposition and inside-out connection is still at work, variously, in most of her recent buildings, such as the MAXXI in Rome.

No one would confuse Hadid with a functionalist; often in her practice function follows structure, and structure follows imagination. At the same time, despite her eccentric shapes, she is not quite a formalist either. Rather, a primary motive of her architecture is the release of forces detected in a given project or site, out of which unforeseen structures and spaces might be developed. Yet this site-specific impulse is at odds with the tabula rasa of her Suprematist abstraction, which prompts one to ask to what extent her schemes are indeed derived from her sites. Consider her Car Park and Terminus in Strasbourg (1998-2001), which is sometimes offered as a good example of site-specific architecture. The outline of this complex follows an obtuse angle, which in turn follows the given intersection of road and rail lines, but the design can also be seen as an architectural abstraction laid over an infrastructural abstraction (Hadid adds a decorative abstraction, too, as she carries the white of the terminus roof over to the car park like a Nike swoosh). In short, the forces here are projected as much as extracted, and one might argue much the same about the braided vectors that make up the MAXXI. Moreover, in architecture no less than in art, the putative extrapolation of a scheme from its site has become a familiar operation; first embraced as a way to avoid the arbitrary, it has become arbitrary in its own way.

Nonetheless, the concern with such forces does point to other historical precedents for Hadid, precedents that her interest in Suprematism and Constructivism has obscured in the reception of her work: Futurist and Expressionist architecture. Sometimes she intimates these affinities in her language. “The whole building is frozen motion,” Hadid remarks of her first signature building, the Vitra Fire Station, “ready to explode into action at any moment”; and generally she has called for a “new image of architectural presence” with “dynamic qualities such as speed, intensity, power, and direction.” What could be more Futurist in spirit than such statements? “Let’s split open our figures,” the Futurist sculptor Umberto Boccioni proclaimed in 1912, “and place the environment inside them. We declare that the environment must form part of the plastic whole, a world of its own, with its own laws: so that the pavement can jump up on to your table, or your head can cross a street, while your lamp twines a web of plaster rays from one house to the next.” As much as any architect since that time, Hadid has responded to this Futurist call for an opening of structure onto space, an interpenetration of interior and exterior, an intensification of “figure” and “environment” alike. Certainly the planar vectors in her paintings and buildings often seem to fly out of a Futurist box of forms.

Just as the Constructivist dimension in her early work grounds its airborne Suprematist aspect somewhat, so an Expressionist dimension in her later work controls its dynamic Futurist aspect somewhat. Some of the forceful geometries that Hadid has proposed since the Vitra Fire Station are modeled in massive materials such as concrete, and more and more she has tended to an Expressionist sculpting of large volumes. For example, the sleek but sturdy profile of her Landesgartenschau (1996-1999), an exhibition hall and research center in Weil am Rhein, Germany, suggests a synthesis of Futurist speed and Expressionist modeling (it both cuts across its landscape and sits heavily in it), and the same is true of her Ordrupgaard Museum extension (2001-2005) near Copenhagen, which also resembles a paradoxically suave bunker, her celebrated BMW plant center (2001-2005), and other recent buildings. Current projects include a media complex in Pau, France, a train station in Naples, and the aquatics center for the London Olympics, all of which evoke Futurist concerns with media and/or movement. Yet Hadid has modeled them, too, as so many Expressionist shapes, and when her Expressionist modeling overwhelms her Futurist dynamism, the result is often a static image.

Indeed, her buildings do not convey movement so much as they represent it — they are precisely “frozen motion” — and, more than a multiplicity of mobile views, they set up a sequence of stationary perspectives.20 Vitra, for example, is effectively a built drawing, a cluster of perspectives made literal, and the interiors of her museums in Cincinnati and Rome also suggest a matrix of designed views, complicated but fixed, and evocative of set design as much as anything else. Minimalism showed us long ago that simple objects prompt us to move about them — in large part to test the ideal forms of our conception against the contingent shapes of our perception. Ironically, with her complex geometries Hadid might arrest her viewer-visitors more than activate them. Moreover, despite the lightness of her pictorial and digital means, there is often a heaviness in her materials and masses. This effect counters the vaunted immateriality of her work; it also leads one to question its rethinking of architectural imaging.

“Which features of the graphic manipulation pertain to the mode of representation rather than to the object of representation?” Schumacher asks. It is an excellent question, one that is hardly restricted to contemporary architecture (it might be the primary epistemological puzzle in visual culture today), yet here it seems a red herring, for, despite the formal complication of the two, Hadid tends to collapse her representation into her objects. Indeed, she seems to use digital technology to minimize material constraints and structural concerns as much as possible, and so to jump from drawing to building as directly as she can. This elision marks a key difference from Eisenman, who worked to thicken such translation, not to reduce it, even as he also manipulated axonometric projection in order to generate his early architecture as though automatically, without apparent intervention by any authorial subject (here he was influenced by Sol Le Witt, who wrote famously of his Conceptual art that “the idea becomes a machine that makes the art”). For her part, Hadid manipulates perspective even more extremely; yet, however distorted and multiplied her perspective might be, it still privileges the subject: artist and viewer remain at the center of the representation-become-building. In short, the displacement of the subject proposed by Eisenman is countered more than affirmed by Hadid (and many others in digital design), and, at least in this respect, the deconstructive line of avant-garde architecture is reversed rather than developed.

Finally, what are we to make, in political terms, of the rapport here with Futurism and Expressionism? As for Futurism, its sexist celebration of power and nihilistic attack on culture are not easily forgotten and not always far away. Expressionism also seems weirdly close today: its expressive values are condoned, even encouraged, in a world of neoliberal capitalism. These may not be problems for Hadid (in any event they are hardly hers alone), yet they cannot be dismissed out of hand. And what about the fate of the other modernisms that she explores? Hadid has carried the utopian visions of Suprematism and Constructivism into the promised land of actual building, yet, as she has done so, she has also diverted them — turned Suprematism away from its radical autonomy and Constructivism away from its materialist critique. Here, too, Hadid can hardly be blamed for reversals that occurred long ago; in the final analysis, however, her relation to all these modernisms is less deconstructive than decorative — a styling of Futurist lines, Suprematist forms, Expressionist shapes, and Constructivist assemblages that updates them according to the expectations of a computer age. Too often, then, Hadid suggests not a formalist whose reflexivity is generative, but a stylist whose signature shapes become involuted and stagnant. In this regard she is finally closer to postmodern architecture than to postmodernist art; the difference is that the ingredients of her pastiche are not traditional styles but modernist forms. In the end, then, Hadid might not escape the accusation that the theorist Peter Bürger made long ago against the neo-avant-garde project in his Theory of the Avant-Garde (1974): to fail in its critique, as the historical avant-garde did, is one thing, but to repeat such a failure — more, to recoup this critique as style — is to risk farce. It is in this way that the neo-avant-garde becomes a gesture.

This point leads to a final one. When Banham urged a recovery of Futurism and Expressionism to guide the architecture of a Second Machine Age (his own Pop period), he did so in part because he felt that postwar architects must be concerned, as he believed those prewar movements were, with the imaging of new technologies. At least in this respect Hadid might be considered a latter-day Banhamite, a paradigmatic designer of our own Third Machine Age of the computer. And one strain in the Hadid literature does argue that her twists, layerings, and interpenetrations anticipated design parameters that have become viable only with recent digital programs — more, that her visionary demands prodded these technical advances into being (Schumacher writes of a “dialectic amplification” between her architectural schemes and computational tools). Along with Gehry, then, Hadid is presented as a prime architect of the digital period. Yet, ideologically, this position is a fraught one, and it has led her associates to dubious pronouncements about the primary purpose of contemporary architecture (“More than ever,” Schumacher asserts, “the task of architectural design will be about the transparent articulation of relations for the sake of orientation and communication”). According to some new-media enthusiasts, critical inventions of modernism such as montage are now absorbed by computer programs as so many automatic options, and this kind of argument has also served to position Hadid at the forefront of avant-garde design. “The model for her work,” Betsky writes, “is now the screen that collects the flows of data into moments of light and dark.” Is this all that it means to further “the incomplete project of modernism”? One hopes that this is not the first and last context for “new fields of building.”

No Comments